Foundations

Presenter: Justin GrantPreparation - please have the following things open:

- TotalTerminal (will popup the terminal when needed)

- GitTraining (https://github.com/jlgrock/gitTraining)

Natural Evolution

RCS

Who remembers RCS? I'm going to bet it's a small number of people.

RCS was a simple version control system that would keep a timestamp and a version for each file. The expectation was that you were dealing with small builds and there wasn't much to do other than keep track of your handful of files. Once projects got big enough to have many files, it became very difficult to check in files one at a time using RCS. So, a wrapper to this was created to handle checking in files en masse.

Natural Evolution

CVS

CVS, the wrapper for RCS, works well enough. We eventually found that, much like FTP, there is a lack of security and it can't keep track of file rollbacks/deletions very well. For example, if you have a file "folder1/abc.java" and you delete it, there is very little to be able to determine what was there before it was deleted, as the server stores this in an "abc.java" delta file, which it then deletes. Also, if you moved "abc.java" from "folder1" to "folder2", it essentially deletes one file and creates it in another place, essentially destroying any history.

Natural Evolution

Subversion, CVSNT

Enter SubVersion. Everyone here should be familiar with SubVersion. First thing, security was increased. SSL and SSH were built in natively, allowing for extremely secure connections. Also, where CVS keeps losing track of files and versioning because it keeps the versioning within each file on the server, subversion applies a version to the entire repository. If you check in "abc.java", the entire repository updates the version to "2.3.758" (or something like that) and can immediately tell you when you are out of sync. This way, even if you move a file (though it has do be done correctly, via the refactor/move commands), it will retain the entire history of a moved or deleted file. Also, you never have to worry about "abc.java" is on v2.3 but "def.java" is on v2.4 - because the versions are cross-cutting.

This worked great and still works great. Subversion is releasing still and people use it all the time. But it still has some problems in our mobile development world. First, What if you are on a long flight or in an institution where internet is unaccessable and you need to work on files - at the end, you might have to deal with a painful merge. Or, you may not have access to history, due to lack of connection to the server. Also, server replication between sites became painful, although still usable.

Natural Evolution

DCVS (Git, Mercurial, etc.)

So why use Distributed Concurrent Versions Systems?

First, it's got a small footprint. Using SHA-1 (a cryptographic hash function), git compares files and only keeps differences. So, just because you made a tag, it doesn't mean that everything needs to be copied. It's just a pointer to a position. Developers should appreciate that and think of this much like a Linked-List pointer. A simple file structure in Git or Mercurial will be easily half the size of a Subversion repository. And that's if you don't count branches or tags.

Your repository is local.

What does this mean to you? It means that start using a repository, I don't have to contact IT. When I have no internet and I need to look through the history of a file, I can do that. When I need to make frequent checkins or rollbacks, I can do that. Also, if I want to synchronize with someone else, and we have no repository, we can do that. Need to check out a tag? You don't need access to the server for that. Also, that means that if there is catastrophic failure, I can work with others directly to get all the latest code.

It's Fast

Because of the fact that DCVS is keeping very tiny changes and keeping them indexed well, it is really fast. If you check statistics, you'll find that these tend to be an order of magnitude faster for all tasks, including initialization, commits, branching, and even running diffs.

It's Here

Not only has Git become the goto for C/C++/Java developers, but is in use for a bunch of other languages as well. It has become the default SCM in the new version of Eclipse/STS. It is available in the world wide web via GitHub, Gitoreus and other similar websites, and it even has tools that plug directly into your operating system so you can version files of any type. It's also available locally. Plus, whether the company wants you to use it or not (luckily ours has been more than accomidating), you can use Git locally. You don't even need a server anymore for version control. Also, using the git-svn bridge, you can use Git with Subversion. This gives you many of the advantages of Git in your current environment.

Setting Up Your Environment

3 Options

- Step-By-Step for each OS

- Download the binary (Make sure to be on 1.8+)

- If you aren't sure you want to install, Give it a Try!

OK, this was a prerequisite to the presentation, so this slide is on here mostly for the folks that viewing this on their own.

Also, side note to those that didn't upgrade, I'd suggest you be on version 1.8+ - it has the ability to cache credentials for all clients. Also, they are changing how outgoing repository tracking is working, and this allows you to set a configuration to keep this as your desired usage.

Setting Up Your Environment

git config

- System - e.g. /usr/local/git/1.7.x/etc/git

- Global (overrides System) - by default, stored in user home directory

- Local (overrides Global) - Project specific, this is stored in the .git folder

Common Commands:

To continue, you must set up your username and email. This is necessary as these strings are stored with every commit. I'd also like to note that user.name is NOT tied to authentication/authorization. Authorization was kept entirely separate to guarantee interoperability.

Past that, these others are just some of the more useful ones:

- push.default - I suggest setting this to "simple". This is something that was found to be a bad design decision, so this is new to version 1.8. This comes to play if you have multiple remote repositories. If you set this to simple, it will only send your changes to one server at a time. Depending on your workflow, this may be different though. For most subversion users, though, the logical one is "simple."

- http.sslVerify - disables SSL Certificate Checks for Git

- color.ui - lets you see colors in your command prompt (like you will see on mine), but will keep those out of commit messages and the like.

- core.editor - lets you specify the default editor, similarly you can adjust your default diff tool

Setting Up Your Environment

See your current commands:

git config -e --global

More Commands:

To see the list of current configurations, use "git config -e" and specify the scope. If you don't specify the scope, this defaults to global. This throws you into your configuration file and you can see and edit what's currently been set.

Create a Repository

git init

OR

git init --bare

Clone a Repository

git clone <url>

Time for your first commands:

- "git init - creates a fresh repository

- "git init --bare" - creates a fresh repository with NO Working directory. This is useful for servers or "blessed repositories."

- "git clone <url>" - Will copy of a repository to your local computer. This includes all history on the tracked branches. What this means is that you need to tell Git what to track. By default, it will track anything you've set up, but not everything. For that you'll have to do a little more legwork. This will be covered in a little more detail later.

We are going to start by cloning a repository (found athttps://github.com/jlgrock/gitTraining). Run the "git clone command" with the url provided on this page.

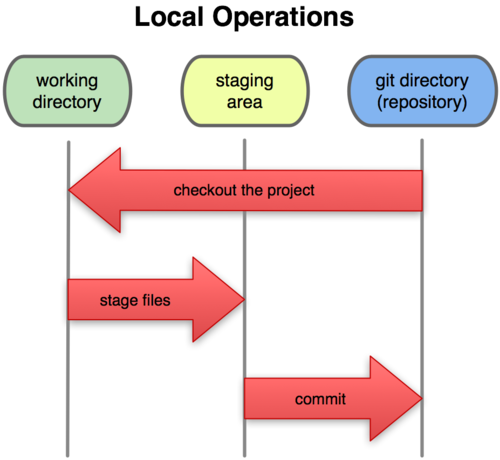

Different Environments - Same Machine

There are three environments on your local computer. I want to make this very clear, as you don't really need to worry about external repositories quite yet. The repository and staging area aren't directly accessable to you. You need to use the git commands to make any changes to those environments. If you want to make a change in your working directory, this is essentially the files that are accessible to you on your file system. Go about your business and edit your files.

In this example, I'm going to adjust the files from the clone that we did in the last slide. Create a file "MessyRoom.txt" in the poems folder. If you make a change to a file, it is done in your working directory.

Add a file called "TimeFlies.txt" with the following content:

Time Flies (Limerick)

By Madeleine Begun Kane

“Time flies” is a popular phrase. So it does, and in frightening ways. Where’s it go? I don’t know. And there’s no way to slow It all down. Simply relish the days.

remember from one of the previous slides "git init --bare" has no Working directory, so this is only applicable to your local computer.

Checking the Status

git status

OR

git status -s

Add the File to Your Index

git add <file>

Commiting Your Changes

git commit -m"<message>"

OR

git commit -a -m"<message>"

Status

run a "git status" to see the current repository's status. You'll see that it shows that there are changes in your working directory that need to be staged. You can also run the "git status -s" to see the short version, if you don't want to see the extraneous messages (because you have seen them thousands of times).

Adding

OK, assuming this is a change that you are going to want, you move this file into your index using the "git add". Similarly, there is a "git rm" command, should you desire to remove it from your index.

Once you have completed the add, do a "git status" again, and you'll notice that the message has changed. There's a section that says "Changes to be committed", which indicates the files in your Staging area. Now, make another change to "TimeFlies.txt" (that's not just whitespace changes). When you do a "git status" now, you should see that you now have staged some changes for a commit, but there are more in your working directory that have to be added.

Go ahead and add those changes and check the status afterwards.

Committing

Now that you've made your changes, it's time to commit. Using the "git commit" command, this will commit any staged files that you changed to your local repository - remember this is local to your computer. Since you haven't given this to anyone yet, you don't have to worry so much about breaking anyone elses code before committing.

The "git commit -a" command is useful if you are making quick changes to files you have already added before (and thus are "tracked"). You will find this useful as you start developing quickly with Git. This is not a wholesale replacement or wildcard for adding, though. Please don't attempt to use it as such.

Review of The Response

How Git Does File Tracking

- Whitespace Ignored

- Timestamps Ignored

CommitResponse

This contains:

- "master" - The current branch

- "root-commit" -

- "87c1a9d" - SHA checksum

- "myMessage" - The comment provided with the commit

- # of files changed

- # of lines added

- # of lines removed

- the file permissions of the file combined with the type of file

How Git Tracks

Git does a SHA-1 hash on the file contents, so you can run the "touch" command. This will trigger Subversion (at least the older versions) to need to commit changes to the file, as this updates timestamp.

In Git, the tracking is oblivious to whitespace and timestamps entirely. Running a "git status" shows no differences.

Branching/Tagging in Git

Create a Branch/Tag

git <tag|branch> <name of tag/branch>

View list of Branches/Tags

git <tag|branch>

Switch to a Branch/Tag

git checkout <name of branch/tag>

Remove a Branch/Tag

git <tag|branch> -d <name of branch/tag>

Now that I've told you how easy it is to make changes in Git, you are going to immediately start checking in a bunch of changes and find that you've gone in the wrong direction on something and need to roll back. It's a fairly common problem.

Git is designed for easy switching of tasks. It encourages you to branch. And since branching is so easy, I encourage you do do it for everything. Every little bug or user story that you run accross. Make a branch for it. They are easy to make and leave such a little footprint that you won't even care that they are around.

"How do I create a branch?" - You might ask... Easy "git branch " + the name of the branch.

"Then how do I switch to it?" - type the "git checkout " + the name of the branch.

For a list of all known branches (on your computer, not remotely), just type in "git branch" with no name following it.

Open Eclipse - show files. Now looking for the only branch in this repository. Switch to it. You'll notice now that when I open files, they need to be refreshed. This is because Git changes what the Working Directory is pointing to. It now points to the reference in the branch and changes layered on top of that.

Switching to a branch moves all of the files in your Working Directory and Staging and lays them over top the new repository view. (Show an example of this.) This makes it quite nice, since you can decide midway through changes that you need a branch for this.

If you are done with it, you can do a "git branch -d" to delete the branch/tag

Merging

git merge <name of branch/tag>

Merge Conflicts

MergeTool

git mergetool

Once you have done some work in the branch, you are ready to merge these changes back. This is much easier that was with other SCMs (especially, older versions of Subversion, for example).

Run "git checkout master" to switch back to the master branch (you can use any branch, but this is common enough), then run the command "git merge " + the name of the branch to merge in.

You don't have to tell the system where to merge from. It will determine where the last common shared code was and use that as the starting point. At this point it will start automatically merging files that don't have line conflicts. If there are line conflicts, it will flag them for you to merge manually.

If you need to merge manually, just use the mergetool command. This is also built into most IDEs, and the diff/merge is a standard, so you can find any number of tools that will help in that regard. Just do a google search for "mergetool" or "difftool" and you can find out pretty easily how to set up your favorite to link to those commands.

Resetting

git reset HEAD

OR

git reset --hard HEAD

Every now and again, your files get a little out of whack. Luckily, if you've been doing what you were supposed to with the branching, you can just blow the branch away and rebranch from the starting point that you want.

Sometimes, this isn't quite so easy though. Either you've been working in the master branch, which can't really be blown away, or you are having a hard time merging into the master branch Note that you can merge into another branch - which is also suggested, as if things go wrong, you can blow it away as well. But I know we aren't all branch-happy yet.

Git Ignore

Git Ignore Templates (By Language)

https://github.com/github/gitignore

I would suggest combining based on development environment and language

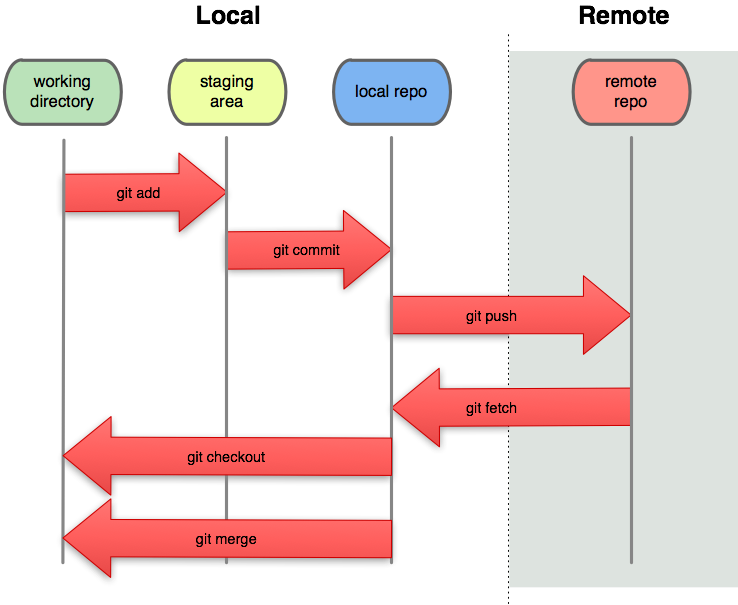

Working With Remotes

Everyone says that there is no master repository in DCVS. These folks are either delusional or trying to pick a fight. We all know that at some point we need to push back to some master. Linus Torvalds (the creator of Linux/Git) calls it the "Blessed Repository". You can call it whatever you want, because there is no difference between that and another repository created on your computer.

Realistically, we need to send these files to and from this repository. Check your current remotes. The "-v" is optional, but I use it to demonstrate that you can have different servers that you get updates from and send updates to.

Working With Remotes (cont.)

Checking Remotes

git remote -v

Add a Remote

git remote add <repositoryName> <path>

Fetching Changes

git fetch <repositoryName>

Merging Changes

git merge <repositoryName> <branch>

If you initialized the repository on your local computer, use the "git remote add" command. This will define one (or more) remote repositories for you to push/pull to. If you cloned, the "origin" is set automatically for you, though you can change it at any time, using the same method.

Once you have specified where the repository needs to get/send the changes to/from, first, use the "git fetch" command. You should always update your code before trying to submit yours.

Fetching creates a temporary branch for you to merge with called "FETCH_HEAD". You can merge with this branch and merge it in using the "git merge" command.

Working With Remotes (cont.)

Pulling Changes

git remote add <repositoryName> <path>

Pushing changes (-u saves parameters)

git push -u <repositoryName> <branch>

OK, so everyone can agree that this gets a little messy with such a common operation, needing to create another branch to merge into every time you need to get changes from a remote repository. So, the command "pull" was made to streamline this. "git pull" will do a fetch, followed by the merge in a branch. If there are no problems with the merge, it's immediately merged back into the branch you are in.

Now we are ready to push our merged changes back to the server. ***Note that if you don't do the fetch+merge/pull first, Git will not let you proceed to the push step.*** Run the "git push" will send the commits that you have done to the other repository, be that in the "blessed repository," or the guys computer sitting next to you.

Stashing

git stash

Applying a Stash

git stash apply

OR

git stash branch <branchName>

One of the most useful tools that I have run accross is the ability to "stash". Git makes you unable to do a fetch or pull when you have changes waiting in your Working or Staging environments. This is necessary, because the tools can't let you mix up revision history. It needs clean breaks in coding. Sometimes, you can't wait for this though. If you do a git stash, it will take all of your changes and put them off to the side for later. Then, it will allow you to overlay these files on the working directory again at a later point. That way, you can stash your files off to the side, do your pull, then reapply the stash, getting you the newest changes without having to create a branch and merge it manually.

To apply the stash, you can either apply it directly to the branch you are working on or create a new branch, using the "git stash branch" command.

You can also name stashes, so that you can have a bunch of them at a time, but that's a little more advanced, and if you need to do that, I'll let you google it for now. But be aware that the option is available.

Caching Your Credentials

git config --global credential.helper osxkeychain

OR

git config --global credential.helper cache

More Information

http://www.sixfeetup.com/blog/git-credential-helpers http://tech.lds.org/wiki/Git_Credential_Caching_on_Mac_OS_X

One of the reasons that I mentioned that you should update to 1.8+ is that this is the first time that all of the different versions (Windows/Mac/Linux/Unix) have implemented the new Credential API. Enabling this will allow you to store your password in the store that makes sense for your OS.

Common Tools for Git

- Supported by all major IDEs (Eclipse/Netbeans/IntelliJ IDEA)

- Atlassian SourceTree (OSX only)

- TortoiseGit

- MsysGit

Here are a few tools to help you in your workflow. Although you don't need these, because the command line helps you out, it's unrealistic to think that everyone would be happy with that. These are the more common ones, but there are a bunch more out there.